The Figure in the Carpet, or, the Utopia of Disappearance

By Christian D. Winkler

By Christian D. Winkler

Ephemera! // Man is but / the dream of a shadow. 1

Pindar. Pythian Odes, 8.

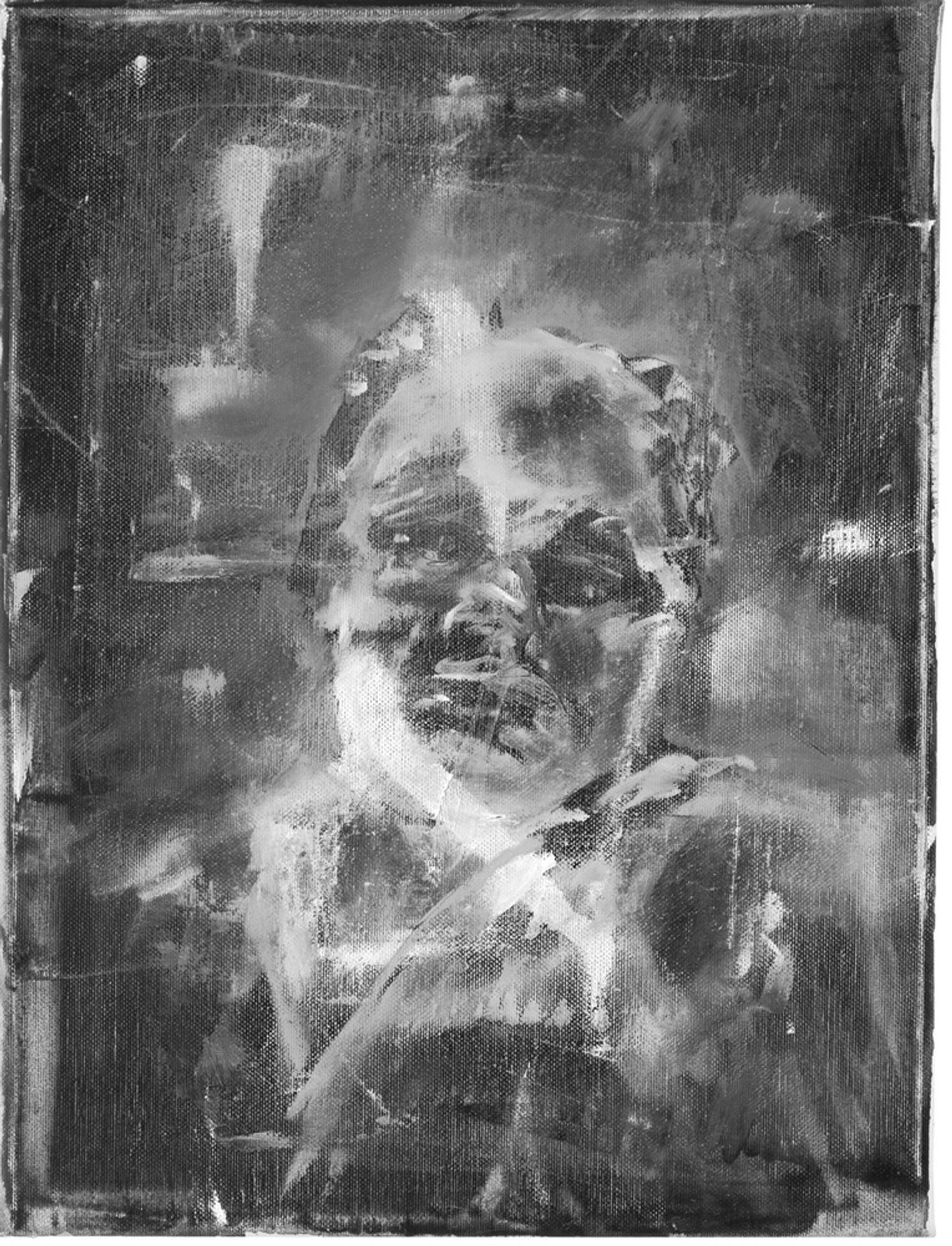

The Fragile 2012, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

His extraneous forms remain, all the technical equipage of artifcial life -

the machines he once conceived, created and set in motion [...]

from being useful to being used up, & ultimately the softest element, conceiver=creator=man.(2)

ONE

Robert Muntean’s works resound like the echoes of vanishing figures (of meaning), consistently composed over and above and beneath and into a roaring rush of colours and forms. In these mostly large-format oil paintings everything living extricates itself from minutely tempered scores of colour, form and texture; it lingers briefly in the apparent quietude of an idyllic clarity, only to submit entirely a few moments later, enwrapped and engulfed by interference that vibrates, murmurs, glimmers sharply, effervesces and oscillates as though there were no tomorrow, or, better still, as though there were no yesterday. Starting out as a whispered symphony of ordered chromatic notes, it is laid down, first cautiously, then turbulently, in resonant planes of form, but soon emerges as a feedback loop in which everything clear, everything orderly, everything contoured disappears in the oscillating distortion of multiple soundtracks overlapping into sheer infinity. A densely woven carpet in broad planes of interlaid and superimposed noise is unfurled across the canvas with sensitively selected threads of colour until the element which functions as the melody in Muntean’s painting rises above the waves of noise: the semblance of a figure.

The figure stuggels to extricate itself from the noise of its surroundings, and while still emerging, while taking on form and contour, the profile just delineated becomes increasingly indistinct until the ego becomes one with the world, until the figure merges with the planes that surround and even: pervade it. 3 There is a vibrant dissociation and dissolution of all things human into the border areas between quiet and noise, rest and distortion, order and chaos. It is ubiquitous in Echoes - the title of this series of pictures by the painter Robert Muntean.

The permeation of metaphors from the visual arts with those from music discourse is legible in the titles of the pictures, which are often inspired by musical concepts from the noise and no wave genres and by lyrics from legendary avantgarde rock bands. But it is also evident in the painter’s working process, where he clearly rises above the artificially guarded and eternally raging opposition between ‘pure’ and ‘conceptual’ painting. Just as a blanket of sound will emerge when well arranged and left to its own devices, so too his carpet of colour. Just as the noise artist is able to expand classical composition techniques for arranging instrumental sound by incorporating industrial noise, the surging hum of the city, or the silence of a forest broken only by the occasional animal call, so Muntean’s sensitive gaze also embarks on a voyage of discovery through the visible elements of the internal and external worlds. Things private and mediated, industrially overloaded and intimately hidden are assembled into a cosmos of motifs where prosaic scenes, mundane observations and the excessive visual density of the advertising and culture industries are abstracted in colour and form by finely nuanced compositional principles.

TWO

Seemingly liberated from the debris of meaning, the chromatic and textual composition of this reality abstraction is so perfectly done that its accomplishment no longer stands out. At the centre of each and every picture is man, or, more accurately, his disappearance. All that remains in a world of global crises, enforced ideological conformity and dehumanising working conditions is the lingering echo of a dissolving subject, the noise, the oscillation, the delineation of contours and, at the same time, the beginnings of the dissolution of figuration. The man who attempts to extricate himself from the confused chaos of his world, the textual complexity of cultural relations, seems to get caught up in the net that calls itself culture.

In diverse constellations of pigment and line and plane, Muntean composes variations on the narrative of the Figure in the Carpet, that topos which was created by Henry James a good hundred and ten years ago and which stands, allegorically, for the incessant search for meaning that makes man what he is. 4 The formulation of a symbolic system of references that facilitates our relational engagement with the world (whilst also arising from it), the development of ordered inward representations of the chaotic ‘out there’, the erection of classical temples and the destruction of enemy palaces, the dogmatic postulating of totalising worldviews and the string of ideologies that seems to want to go on for ever: ego, god, state, property, nation and foreignness, but also the development of the arts, human rights, pluralism. In short: the figure in the carpet owes its existence to but also attempts to break out of the great, broad and ever-expanding network of culture - out of the densely woven chains of tradition, the constant reminders of the past, togetherness and solitude, empathy and detachment. And at the same time, having finally attained his freedom, grasping around for support and networks of order, the figure realises that the knots that hold his identity together are starting to come undone. The figure in the carpet, of whom Robert Muntean composes variations, forgets that he is the spider that weaves the net as well as the net that bears the spider. 5

THREE

The carpet from which animate things grow is the world. The figure that orginates from it is man. He takes hold of the loose, chaotic threads and ties and binds them until, from the loose weave, the ball of wool that is the world, he has knitted himself together and ultimately become entangled in it. He contracts agoraphobia, feels trapped and chained by the threads, the strands and weals of meaning. He starts thrashing about as though he were out of his senses, ripping and weeping until that very mesh of knots - tears apart. And he falls: out of the frame, off the edge of the carpet, into the ray of light and, accustomed as he is to the darkness of the carpet-cave, he is blinded. He loses sight of himself - and falls.

The figure emerging from the carpet hovers. Behind, before, within the coarse form of the world. His identity, his profile, his whole great clear self is obtained only by knotting and sealing off semantic connections, from open threads to closed nets. The more he tries to escape the closed weave of tied knots, the happier he is that he himself is not the weave, the net that radiates in all directons without centre or sense. The carpet, which is the world, is the diversity of colours, the chromatic chaos towards which the figures lapse all the more the more they attempt to alight. And the carpet, which is the world, is distorted noise, feedback from the roar of an atonal world.

Maintaining for a moment the analogy of the carpet of noise (tone or sound) and the carpet of colour (form and texture), and keeping the topos of the carpet figure in mind, Muntean’s paintings opens up a philosophical discourse which, at its core, goes back to the concept of the ‘atonal world’. 6 According to a thesis emanating from the sphere of post-structural theorems, the world is atonal, a ramified rhizomatic texture of simultaneous and equally valid sounds. 7 Critcism of the (Oedipal) emergence of subject and culture along tonalised, i.e. hierarchically preformed lines is combined with the protest against the clear order of one-dimensional, functional conceptions of man in modern industrial society. A longing for intellectual liberation and plurality confronts the ever-growing shadow of authoritarian systems of politics and thought 8 in the supposedly post-totalitarian age. 9 The world we live in, so it goes, knows no tonal scale, it no longer knows any system of order that might be capable of imposing upon the noise the tonal corset of a dogmatic understanding of world without opening itself up to the charge of being constrictive, artificial and arbitrary. The world we have to live in is pluralistic, tolerant, value-free and out for a levelling of hierarchies and gradients of domination; what we are leaving behind is the tonality which dominated for so long and which we arduously extricated from the chaos to the point where it became totalitarian and developed into a principle of world order, forming a worldview which sought to explain things which could not be explained. For those who subscribed to it it suggested a closed view that promised a pleasantly soft security and turned out to be manacle. It declared war on those who did not.

The figures in Robert Muntean’s pictures are the children of atonality. The rhythm of the mother’s heartbeat vanished at birth with their introduction to the polyphonic world. 10 There is no longer a leading note, no baton determines the movement. The animation of life is open and free. The children of atonality look for their melody in the chaos of the world and yet they know that their lot is the freedom of those who can no longer return to the coherence of a predetermined heartbeat. And moreover: they abhor the tonality of a prescribed world and the wish to return to the before of the post-ideological age, they abhor the dogmatism of religion, the glorification of redemptory political doctrines and the remnants of aberrations from pre-Enlightenment times. They acknowledge the impossibility of positing stable semantic structures, and yet they seem to lose their contours, their posture, their strength, as though they were disappearing along with the disappearance of the great political utopias. A lack of ideas and visions proliferates in the minds of the serenely enlightened. Resignation sets in - as in the leitmotif of the picture Disappearer (Brian Wilson) - no more highfalutin projects for a better world, no emancipatory visions that might be capable of counteracting predatory global capitalism, the dictates of the market, compensating for a lack of guidance by longing for a leader, through recourse to ideology and fundamentalism; they disappear in the chaos and from the chaos of a rhizomatic, atonal world.

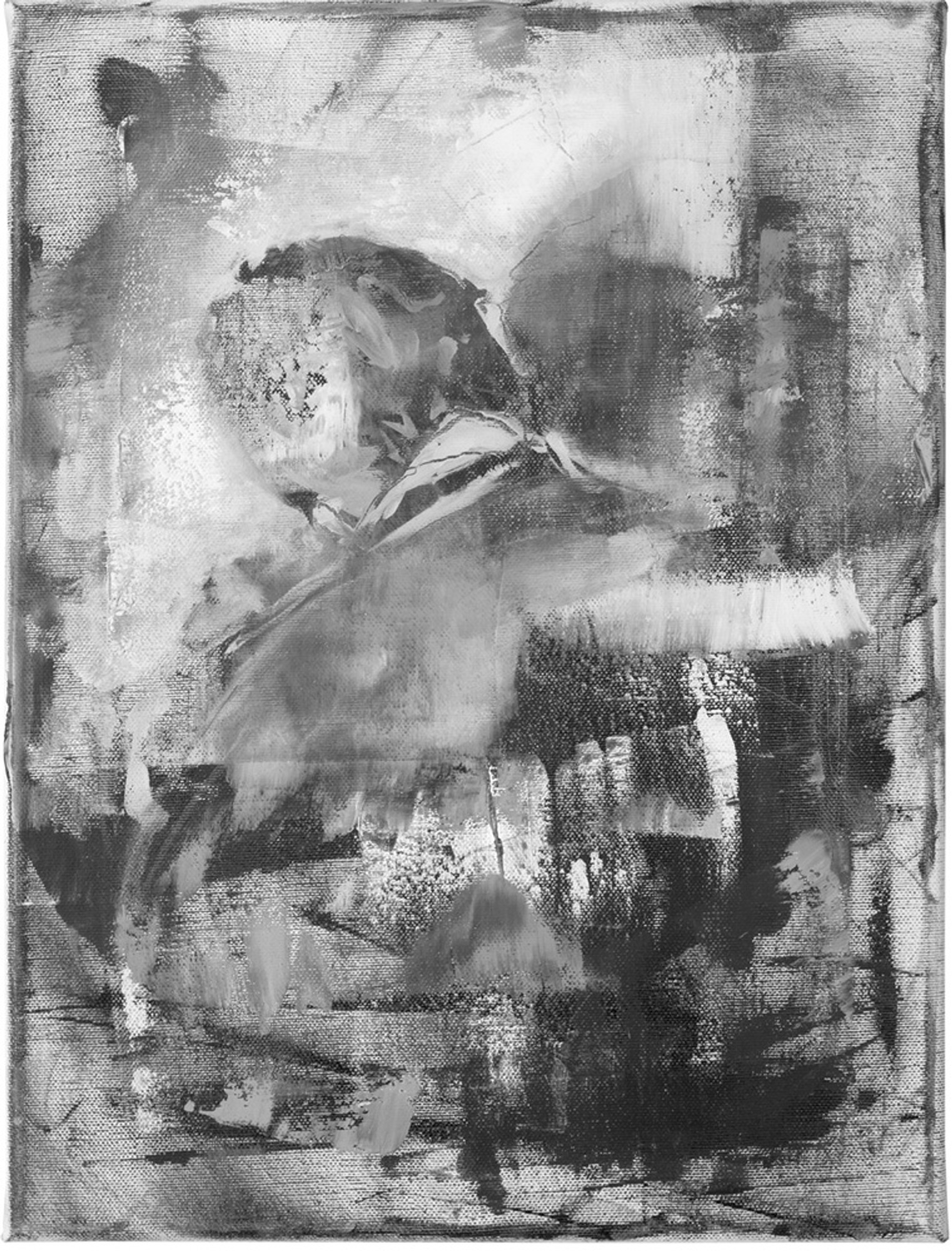

Kesey 2012, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

FOUR

Human figures oscillate on the residues of colourfield geometries in constant projection, recession, transparency, being visible and disappearing. As if an already adumbrated world were inundated by the waxing and waning effervescence of the poles, as if a hurricane were drowning out the regular course of prevailing winds, as if the broken glass were mirrored in the approaching distance, shimmering through the frames and edges of a coherence long since overcome. The clarity of a system of reference sinks in the spume generated by the angles of elevated flowing movements.

The disappearance of those grand narratives whose framework once made everything seem so clear and simple, the disappearance of the credibility of grand redemptive utopias and the all-too justified scepticism with respect to ideology and prescription (of thought) releases Muntean’s figures into a open, stormy sea whose erupting surf thrashes around and threatens to swallow up all forms of orientation. There is no island of the blessed for which the broad horizon is closed off, no driving plank that is not already decaying, putrid and rotten, in the darkness of coherent worlds.

But the floods that engulf Muntean’s figures are not just the crashing waves of an atonal world, not just the carpet they emerge from, holding onto the knots they tied in its threads; they are always also - the figures themselves. The ordering, world- perceiving, world-viewing and world-appropriating instance is man; the carpet he weaves is of course a depiction of his design, a regulatory over-painting of the unpainted. But Muntean’s carpet is a step ahead: what he depicts is not primarily the outer world become atonal, but rather the self-extrapolating, self-revealing inner world of the figure.

A diversion of the gaze from everything external, that introspection or even self-absorption which is so often ascribed to his paintings, is not in fact the case here: his figures may look as though they are at repose - and there is often an overwhelming temptation to submit to these moments of introversion, to the all-encompassing contemplation of timeless contemporaneity in the act of beholding - and yet one cannot get around having to acknowledge how much of the inner life of these figures flows to the outside as though they were disgorging themselves, inexorably exploding onto the canvans in a virtually expressionistic manner. The figures are so extroverted that their most intimate selves begin to disband. When Muntean extricates his figures from the planes their indistinct bodily contours push outwards, the merge with their surroundings and become - or rather, are always already - one with them. In his characteristic mode of painting there is obviously no formulation of clear froms - the spiritual state of the ego is transferred onto the canvas as a fragile state of corporal being.

What becomes visible when the inner world turns outwards is the atrophy of clear forms, the loss of ordering principles, an anarchy of colours and forms. ‘If there were no people in the pictures one could just as well paint something completely geometrical’ 11 - but since the people Muntean paints are not only that instance which longs, perhaps secretly, for order and geometry, but also that to which these things are denied, every attempt at ruling and framing evaporates: the straight lines, ellipses, trapeziums and polygons that Muntean often suggests remain mere suggestions; regardless of whether man considers them true or false, all facts turn out to be human desires projected from a vibrant state of diffusion. The wish to reach out and to grasp things throws the certainty of geometry off kilter. This meaphor, which Muntean explicates where he speaks of a division of forms into chaotic-animate-organic and clear-inanimate-geometric is a further index for the central pervasiveness of the search of meaning. The mere presence of man as agitated animate chaos is enough to demolish those imperishable primal forms and their increasingly prevalent ordering phenomena. The unattainable in geometry, that ultimate system of order and stability, is the plane of longing that shines through man without being clearly tangible.

FIVE

The dimension of time is fundamentally more important than space for Muntean’s painting. In a time-consuming sequential painterly process, layer is laid upon layer until the uniquely grounded surface betrays a past that seems to be hidden way back in the lower levels. Light in places, ochre in others, nutty wood here and pearl-copper browns elsewhere, the many shades of pigment that make up the earthy substrate - evident, for instance, in Andre Sider, Echoes, and the Sub rosa cycle - recall past and present layers of earth that have been sedimented over the centuries into the solid matter upon which we now stand and upon which we establish our existence (here, the well-known Foucauldian metaphor of an archaeology of layered time, an archaeology of history, could be further developed.) 12 It is not the various political circumstances of changing socio-political systems that are (were) sedimented in the temporal layers of culture (world, carpet, noise), but the fundamental structuring patterns that impose order on society. Muntean’s layers of time point to precisely that aspect of Foucauldian discourse analysis which sought to visualise the timeless structures of power and impotence, forms and mechanisms of dominance and being dominated, in the deeply sedimented archaeology of the knowledge of collective memory. Man emerges from the fine laminate of its layers, becomes visible, becomes one with them, then disappears.

When the Greeks spoke of man as the epitome of ephemerality, 13 fleeting like a butterfly, subject to constant transformation, a thing for a day, they recognised a state of affairs that coincides with insights from contemporary neurophysiology as to the evolutonary adaptability of the human brain. The most stable elements of man are his organs, his bones, and even these ultimately and inexorably tend towards nothingness. But the mind is an accumulation of experiences, beliefs, attitudes and memories that are ‘formed and reformed by changing events and circumstances’ 14 and are precipitated throughout the history of mentality, but worn away like sandstone in the tide. The doggedness of ideological adherence to a stable and comprehensive experience of one’s own ego, to the reliable consistency of our temporal existence, is contrasted in Robert Muntean’s painting by figurations that disappear instead. His figures are metaphors for the waning of stable identity concepts and, what is more, they are illustrations of the philosophical insight into the impossibility of positing stable structures of meaning. But though Muntean’s paintings are borne along by doubt, though his paintings imagine a world from which man emerges, though they acknowledge the fundamental critique of a humanism that idealises human nature, the fundamental core of his pictures is nevertheless: humanistic. (Immediately after the second world war, the critique of humanism developed into a controversial philosophical debate between Heidegger’s critique of metaphysics and Sartre’s conception of an existential humanism. Ultimately it gave rise to the French school of post- structuralist philosophy, which Muntean draws upon heavily. It spoke of the ‘end of man’ or the ‘death of the subject’). Anything apocalyptic, inhuman, misanthropic is foreign to Muntean; one of the central, if not the central leitmotif of his painting is a respect for the seeking beings we are, for those who go astray, make their own way, see it peter out and then move on again. His sympathy for man’s state of having been thrown headlong into a senseless world is direct, from the heart, and comes as a fraternal conciliation for all who give themselves up to their headlong flight without clinging to the allure of redemptive dogmas, whether worldly or spiritual.

Ono soul 2011, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

SIX

The disappearance of man- and this, for me, is the decisive core of his painting - happens in the very first instance, that is, before the context fades out or away, in quite specific surroundings and in an environment that is neither arbitrary or vacuous, neither chaotic nor colourful, but concrete. The seemingly eschatological vision of a disintegrating human identity takes place before the historical background (one where- to use the language of images - the archaeology of culture is layered into the background) of totalitarian anthropological concepts from pasts that are still alarmingly present. The world from which Muntean’s figures emerge is that of a one-dimensionality that imposes limits on any form of individuality, 15 it is imposed on the free developmental will of human identity as a prescribed template of conformity. Totalitarian systems - whether religious dogmas that lay claims to the absolute, politically collectivist dictatorships or the tenacious market dictates of neoliberalism - are more than just systems of rule; they are designs for life that seek ‘to shape, according to a dominat ideology, private life, the soul, the intellect and the customs of the addressees of power.’ 16

The environment from which Robert Muntean’s figures disappear is a world that man has fabricated to the point where there is no longer any room for man himself within it. The world from which these figures disappear is a dehumanised world in which the socio-political, economic and hegemonic contexts leave no room for a joyful, peaceable subject. Though now reduced to a mere phrase, this was Adorno’s central fear, namely the impossibility of a correct life under false conditions. In this light, the possibility of Muntean’s figures finding their meaningful place in the world looks slim. The abovementioned utopia of eschewal propounded by Brian Wilson (who lived up to the topos of the dropout by refusing to get out of bed for six months and preferring to indulge his own madness rather than pursuing any sort of socio-political involvement with the existing situation) epitomises precisely that resigned undertone of a generation which is at risk of going astray and losing its faith in engagement within an open, pluralistic society.

In this sense, Muntean’s paintings are a demand for the tonalisation of the atonal world. Taking up a position that stands out markedly from the ramified rhizomatic texture of the world is nowhere more important than in our present pluralistic society; nowhere else is it as important to speak up before the ideologues of dogmatism manage to transplant the seed of the open society into new tolitarianisms that are grounded in the manure of the old, opening the door to the complete disappearance of humanity. Only here is the sum of sensual and corporal cultural realities an unheard-of confusion of shattering sounds which is not in a position to impute to the value-free world a value defined by attitudes rather than numbers. ‘One has to find some way to confront [the atonal world], writes Slavoj ŽiŽek in his attack on the basic pillars of post-structuralism, with the fact that it is compelled to tonalise itself and has to concede that its atonality is held up by a hidden undertone.’ 17 The atonal world needs invented sonic beauty, or rather, ‘lost causes’ demand the taking-up of positions (ŽiŽek).

Knowledge of the impossibility of a firmly posited meaning only has a liberating potential when accompanied by the konwledge that positioning is a necessity. With Muntean, it is precisely this potential for setting new but never imperative accents within the noise of indistinct contours that transforms the dystopia of the disintegrating subject into a utopia of the disappearance of petrified structures. The lightness of the brushstroke dissolves the impasse and opens (up) a space (now not nearly as unthinkable) where there is again room for the belief in the possibilities of intervention.

For the hegemony of the ideologies of the dominant global economic system, of post-totalitarian nations and global power structures is ultimately only perpetuated by the tacit acquiescence of each and every individual - the perpetuation of societal functions 18 which were fabricated by man just as much as they now threaten to displace him. Muntean’s painting redeems what Adorno described in his Aesthetic Theory as the societal function of art: having no function. Or in other words: destabilising societal functions. An awareness that the political subject is actually able to intervene in the conditions of societal reality, but that art can provide neither answers nor political analyses, that it can neither bring about a deheirarchisation of power structures nor participate in the revolutionary cannonades of the resistance fighters, is evident precisely where stable structure is allowed to disappear; in the task of art: bringing chaos into order. 19

SEVEN

Almost imperceptibly, Robert Muntean confronts the aesthetics of appearance with an aesthetics of disappearance in which the effects of a dehumanised world are made visible. With the ancient means of ‘pure’ painting Muntean creates a ‘conceptual’ visual reality that turns the disappearance of utopias into the utopia of disappearance. With painterly ambiguity and without any of the pathos of those who confuse slogans with art, he gets to the heart of the whole tragedy and the unshakeable hope in a pluralistic society divested of ideology. To some it is refuge of high aestheticism in form and colour offering hours of immersion in a romantically placid counterworld of reference-free painting. At the same time, it also contains highly political metaphors for the condition of an atonal world.

Notes

1 Pindar. The complede odes, trans. by Anthony Verity with an introduction by Stephen Instone (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007)

2 At this key point in his epochal novel, Die Stille, Reinhard Jirgl evokes the work of the prominent Japanese photographer Naoyo Hatakeyama, whose works may here serve as a acid reference to the following thoughts on Robert Muntean. Reinhard Jirgl, Die Stille. Roman [Silence. A novel] (Munich: Hanser, 2009), p. 495. This passage is printed with the kind permission of the Hanser Verlag, © 2009 Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich.

3 This ‘process of painting layer by layer’ (Max Benkendorff) and allowing the planes to run establishes the ground from which the oscillating rudiments of a figure emerge. Max Benkendorff refers to this process in his accompanying text to the 2007 catalogue, Without a sound. See Max Benkendorff, ‘Der Gebrauch der Malerei’ [The application of painting]. In: Robert Muntean - Without a sound, (2007)

4 Henry James, The Figure in the Carpet, (Rockwill: Wildside Press, 2003).

5 See Jean Baudrillard, Why hasn`t everything already disappeared?, trans. by Chris Turner with photographs by Alain Willaum (London, New York: Seagull, 2009).

6 As far as I am aware, this concept first occurs in Badiou. As an avowed communist and thus representative of a concrete (redemptive) ideology, he was sceptical as to the possibility of a pluralistic, fragmentary mode of world appropriation without any sort of ordering strategy. See Alain Badiou, Logic of worlds, (London: Continuum, 2009). The concept is given further consideration towards the end of section six of the present essay

7 The well-known anti-Oedipus myth of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari is directed the Freudian attempt to apply individual psychology’s Oedipus myth to the orgins of cultural history. Instead of the resulting inevitability of the formation of hierarchies in the sense of a family tree growing downwards, they argue for the conceivability of an egalitarian model of the rhizomatic texture of the world - that is, a texture that grows in breadth - whereby subjectification along hierarchically preformed lines could be negated. See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: capitalism and schizophrenia I, trans. from the French by Robert Hurley (London: Continuum, 2008).

8 In one of her books, the cultural scientist Aleida Assmann has investigated the mental repercussions of totalitarian repression, establishing a latent longing for closed edifices of thought. See Aleida Assmann, Der lange Schatten der Vergangenheit. Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik [The long shadow of the past: commemorative culture and the politics of history] (Munich: Beck, 2006).

9 The prefix ‘post’ here refers to the latent after-effects of former totalitarianisms, and not their having been overcome. See Hans Maier, ‘Totalitarismus und politische Religionen. Konzepte des Diktaturvergleichs’ [Totalitarianism and political religions: concepts in the comparison of dictatorships] in Totalitarismus im 20. Jahrhundert. Eine Bilanz der internationalen Forschung, ed. by Eckhard Jesse, 2nd edn (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1999), pp. 118-34.

10 See Peter Sloterdijk. ‘Klangwelt’ [Sonic world] in idem, Der ästhetische Imperativ. Schriften zur Kunst, ed. by Peter Weibel (Hamburg: Philo & Philo Fine Arts, 2007), pp. 8-82.

11 Robert Muntean in conversation at his atelier in Berlin, late April 2012

12 See Michel Foucault, The order of things: An archeology of the human science, (London, New York: Routledge Classic, 2002). In this investigation Michel Foucault attempts to determine the structure of thought in a specific epoch in order to gain insight into the ‘silent order of things’ and ‘the historically specific epistemic logic or general order of knowledge in a certain epoch’. [Philipp Sarasin, Michael Foucault. Zur Einführung [Michel Foucault, an introduction], 4th edn (Hamburg: Junius, 2010)]

13 The antiquary Hermann Fränkel points out, among many other things, that early Greek culture considered the human mode of existence as ephemeral and men as ‘ephemera’ - as transitory phenomena, things that exists for a day. Precisely this insight is reflected in the odes of the classical poet Pindar, for instance in the following lines: ‘Man is but / the dream of a shadow’. See Hermann Fränkel, ‘Ephemeros als Kennwort für die menschliche Natur’ in idem, Wege und Formen frühgriechischen Denkens [Paths and forms of early Greek thought], ed. by Franz Tietze, 2nd edn (Munich:Beck, 1960), p. 25.

14 Ibid.

15 See also Herbert Marcuse’s analysis of the conception of man in capitalist society: Herbert Marcuse, One-dimensional man: studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society, 6th edn, Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press 1969

16 Karl Löwenstein, Verfassungslehre [Consitutional theory], 2nd edn ( übingen: Mohr, 1969), p. 55

17 Alain Badiou’s scepticism about an ‘atonal world’ (mentioned in section three above) undergoes its inversion here. See Slavoj ŽiŽek, In defense of lost causes, (London, New York: Verso, 2009), p. 31.

18 In his social ontology, John Searle, after a logical analysis of social reality - one that is not entirely detached from the Marxist belief in the alterability of being (economic, political, etc.) by the force of consciousness - comes to the conclusion that societal reality and with it the system of trade, governance and being governed, society and social interaction are all acts of human postulation and thus only exist for as long as a sufficient number of their actors continue to support those postulates. See John R. Searle, The construction of social reality: on the ontology of societal facts, (New York: Free Press 1995).

19 See Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic theory, trans., ed. and with a translator`s introduction by Robert Hullot-Kentor, (London, New York: Continuum 2002).