The Noise of the Tabelaus

By Oona Lochner

By Oona Lochner

You know that something must be wrong

in the patterns of narration from right angles,

missing corners to hereditary transgression

becausecausecause and always becausecausecause 1

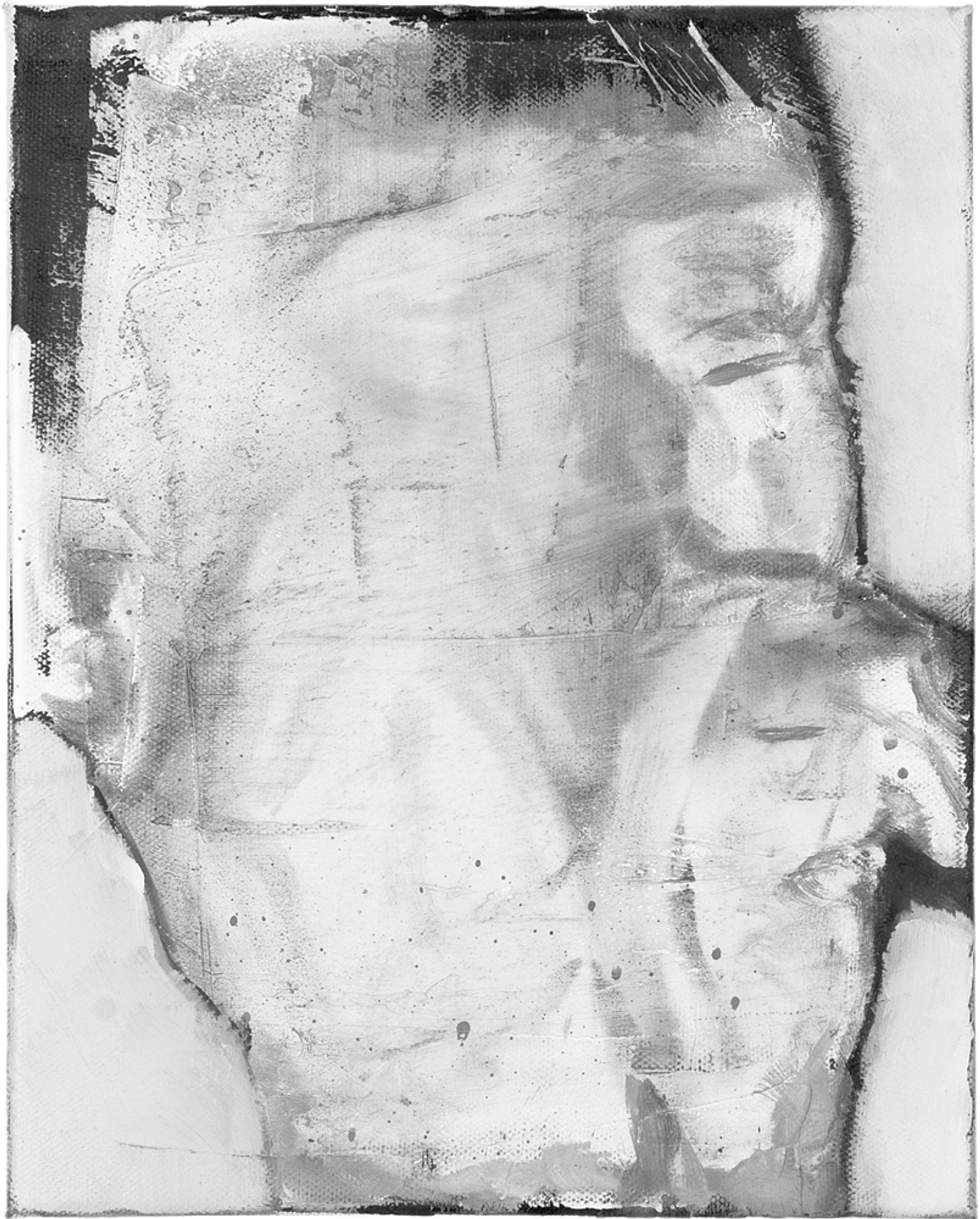

Singer 2010, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

Robert Muntean’s paintings are generated out of the tension between objectivity and abstraction, between immediacy and process. The central and pivotal point of his painting is the figure, though it consistently eludes the expectations of Figurative painting; Muntean’s figures baulk at absorption under the concepts of representation or a superordinate narrative. They generally appear in isolation, but even when there are several people there is barely any interaction among them or with the viewer. Surrounded by abstracted, ambiguous spaces, they remain introverted, giving away little of themselves and their stories. There is perhaps a certain, often melancholic mood that can be felt in the attitude and countenance of the figures, but the paintings can scarcely be read in terms of a concrete situation or narrative.

The severe narrative reduction of Muntean’s painting is all the more astonishing for the fact that its protagonists mostly stem from quite concrete contexts. The motifs are taken from personal photos and media imagery of pop culture from magazines, films and the internet. Blixa Bargeld, Joy Divison and Beach Boys songwriter Brian Wilson alternate with film characters such as Quint, Brody and Hooper on the hunt for their great white shark. And there’s art historical material in Muntean’s repertory too: Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings on cardboard, portraits by Max Beckmann or Édouard Manet’s ‘ The Execution of Maximilian’ (1868/69). It’s not so much the actual stories of these figures that Muntean incorporates into his pictures; it’s their posture, their countenance and the mood of melancholic withdrawal they suggest. Once disassociated from their genesis stories the protagonists again find themselves in spaces whose fragments are often also taken from pre-existing imagery. It’s not the recognition of definite places but the forms and structures themselves that are foregrounded here, such that a flooring pattern might be turned into a ceiling construction and windows or corners of rooms condensed into abstract planes of colour.

But though the spaces and identities of the figures are lost in these paintings, there is an implicit confrontation with visual sources that takes place in the background. The frequent recourse to musicians belonging to the various countercultures of the 1980s opens up a play with the „otherness” of the artist - a cliché that also fed into the debate around neo- expressionist painting in the same decade and has ultimately remained effective in both cultural spheres up to the present: the myths of the eccentric musician and the artist genius coincide in the idea of the artist withdrawing and distancing himself from the bourgeois world, eschewing its norms and expectations in order to defiantly oppose it through art. 2 Muntean does evoke this stereotype with his choice of motifs, but the figures begin to shed these attributes on their path from pre-existing media imagery and into his paintings. By disassociating them from their contexts and transposing them into ambiguous abstract spaces he strips them of their identity and shatters the moment of representation along with the mythical charge of the artist personality. All that remains is a subliminally resistant attitude of introversion where formerly individual persons become types; representatives of all those who struggle to find their place in the world while eschewing certain aspects of it. The reflection and repudiation of the world here is by no means the privilege of the artist.

That this type of contemplative objector can even be evoked in the form of a figure from an advert (Let’s move to the country) casts light, on the one hand, on the way in which the motifs and postures of a counterculture are transposed into different, commercial contexts. On the other hand, Muntean’s own eclectic approach to the images that surround him - combining the public and the private, the subcultural and the commercial - reflects the mobility images have attained through Google, Facebook and Pinterest. But while for them the proliferation of images serves to link as much (commercially valuable) information as possible to the image connected with the person, Muntean dissolves this association, reversing the process by abstracting his figures from the individual. His works thus nourish a certain scepticism as to whether the hegemony of consumer culture can be effectively eschewed, but they also frustrate the customary logic of images in circulation. In this much, figures drawn from the context of 1980s New Wave, No Wave and Rock - bands such as Joy Division and Einstürzende Neubauten - are more than just visual types for Muntean. Incorporating experimental and electronic elements, their music also finds parallels in his own painterly work. The open guitar tunings of Sonic Youth or the sounds and noise employed as musical means by Einstürzende Neubauten; both stand in connection with the optical noise that proliferates in Muntean’s painting. If one conceives of musical and painterly figures as being related, as the artist does, then the latter is the melody recognisable within the picture: In Muntean’s recent works the figure increasingly dissolves into the visual noise of flecks of colour. Facial features and corporal forms become unclear and start to shimmer over the background. This increasing abstraction is already prefigured in Hyper, Hyper. A female figure stands turned toward to the viewer on a vague blue-green ground in front of two walls that are pushed together perspectivally. A broken line describes no more than her legs; her head and arms are made up of flecks of colour set down next to one another. The torso consists of a short, red-brown dress, its colours sketched in broad brushstrokes that are so transparent as to lie like a thin film over the planes of the background. Rather than solidifying into a single volume and establishing a relationship to the pictorial space, the faceless, bodiless figure flickers above the uniform background as though it were interference or a hologram, or a solitary, trembling note.

Jungle 2010, oil on canvas, 30 × 24 cm

In other pictures, though, as in the large format work Echoes (after Manet), the background also dissolves into restless flecks of colour such that figure and pictorial space coalesce into the same noise. The vertical body of the standing figure is set against the smeared, intermingling tones of the background as nothing more than a transparent form, the outlines marked by a blue-green glow reflected from various points of the surrounding space. The echo in the picture’s title is realised in the reverberation of the colours. Just as a recognisable figure now and then stands out from the blanket of sound produced by Einstürzende Neubauten, here too the object briefly emerges from the background before immediately merging back into it. Lifting itself out of the noise as a lucid and fragile form, the figure describes a brief moment in the process of painting that maintains a tension between clamour and quiet.

The signifcance of temporality and process for Muntean’s painting is also particularly legible in Rome. The pictorial space is loosely articulated in depth by three areas of colour applied in blue, yellow and red-brown glaze. Similarly feint lines suggest the outlines of two figures in the middle ground and the form of a monument behind them. It is only in a second step that Muntean applies more pastose areas of colour, sweeps and smears that lend the bodies solidity and volume while still allowing them to flicker in front of the glazed background. This working method produces on canvas something similar to the luminosity Muntean also achieves in his works on paper. At the same time it creates a tension between the various ways of applying paint: feint planes of heavily diluted pigment are contrasted with the areas of colour that Muntean applies with a broad brush, a spatula or directly form the tube, sometimes spreading it out by direct intervention on the canvas, when he wipes wet paint away here and there or draws hard ridges through it with a squeegee. Without the painting process having been planned in detail, these individual placements are nevertheless calculated and always made in response to what is already there. Paradoxically, the clearly momentary element of painterly placement is firmly anchored in the process of pictorial invention. Neither the interventions on the canvas nor the smearing of paint directly from the tube are to be understood as impulsive gestures that might have been intended as some sort of expression of an inner state in a modernist, expressionistic sense. Rather they are the ciphers of an immediacy that Muntean posits precisely in order to expose the involvement of the individual gesture in the painterly process and thus to emphasise the working process over the work. 3

In an entirely similar way this is also the focus when Muntean makes new versions of the same motif again and again over the years. The young woman turning her back to the viewer, the sleeping or awakening figure shielding his eyes with both hands, the head of a young man sunk on his chest; each of these motifs is repeated in multiple variations as in a piece of music. And the titles of the paintings are repeated too - Sub rosa, Closer, Echoes - though they don’t necessarily refer to the same motif each time.

The idea of the completed work is pushed aside in favour of the production process and, just as selecting the motif from the sea of media images is crucial to Muntean’s work, searching and feeling around for new forms also takes on its own significance. More important than the motif itself, it seems, is the question of how to approach it through painting and why the answer to this question is always different. Repetition doesn’t always produce the same thing, but rather change time and time again. Like memory, which shapes and concentrates an event in its multiple recollections, so too the repetition of the same motif condenses the already reduced narratives in Muntean’s pictures such that the form disassociates itself all the more from the original context of the figure. His systems of reference, the stories narrated and thus also the meanings of his images remain diaphanous.

With their references to pop culture and to the way images are currently used, Muntean’s works present a claim to be constantly renegotiating the relationship to their own social and cultural context. At the same time they pose the question as to how painting can mediate this today and fathom the possibilities of a painterly narrativity and referentality.

Notes

1 Einstürzende Neubauten, ‘Weilweilweil’, in: Alles wieder offen, Berlin, 2007

2 According to Niklas Maak, ‘without fail, press reports describe Neo Rauch as the lonely hermit of his Leipzig woolen-mill atelier`. He gives a list of other examples. Niklas Maak, ‘Manufactum on Canvas. On the widespread success of figurative painting`, Texte zur Kunst 77 (2010): 117-121, here p. 118.

3 Martin Kippenberger’s early work is described in similar terms by Isabelle Graw in ‘Conceptual Expression. On Conceptual Gestures in Allegedly Expressive Painting, Traces of Expression in Proto-Conceptual Works, and the Significance of Artistic Procedures’, in: Alexander Alberro/Sabeth Buchmann (eds.), Art After Conceptual Art (Cambridge, MA, London; MIT Press, 2006). pp. 119-133, here p. 128.